All Hunter knows of the morning of January 2, 2020 is what his friends and family have told him.

The 17-year-old was at Franklin High School, the first day back after winter break. The bell rang at 7:20 a.m. Hunter was sitting in room C213 for social studies, first class of the day. His teacher, Ryan DePouw, was talking about the Pacific campaign of World War II.

8:02:59. Suddenly and without the slightest warning, Hunter loses consciousness.

For the briefest of moments, everything stands still. Then instincts and training kick in.

Ryan runs over to Hunter, slumped over in his chair, and checks for a pulse. Finding him unresponsive and not breathing, he shouts for a student to run to the administrative office and get help. Another student pushes the emergency response button, which causes a phone to ring in the administrative office with a special emergency tone.

When someone goes into sudden cardiac arrest and stops breathing, every single second is crucial. Every tick of the clock can mean the difference between a full recovery, brain damage or even death.

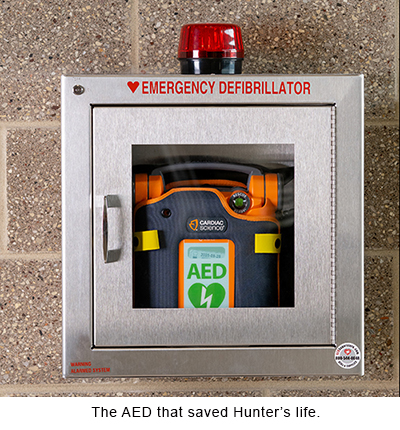

8:03:43. Jordan Hein, athletic director and a member of the school’s emergency response team, arrives in the classroom. As Jordan gently lowers Hunter to the floor and assesses his condition, Ryan runs to get an automated external defibrillator (AED) from down the hall.

8:03:43. Jordan Hein, athletic director and a member of the school’s emergency response team, arrives in the classroom. As Jordan gently lowers Hunter to the floor and assesses his condition, Ryan runs to get an automated external defibrillator (AED) from down the hall.

8:03:50. Five more members of the emergency response team arrive.

8:04:05. Ryan arrives with the AED.

8:04:40. As Ryan calls 911, another member of the emergency response team places the AED sensors on Hunter’s chest and they start evaluating his heart’s status.

8:04:50. The team begins chest compressions and rescue breathing.

8:07:05. The AED delivers the first life-saving shock.

8:09:15. Outside, the Franklin Fire Department pulls into the school parking lot.

8:10:01. Five firefighters arrive in the classroom.

Seven minutes. 420 seconds from the time Hunter lost consciousness to the time the first responders arrived on the scene — a remarkable response to a medical emergency.

Every year, more than 350,000 lives are lost due to sudden cardiac arrest in the United States. On average, if someone has a sudden cardiac arrest outside of a medical setting, they have barely a 10 percent chance of survival.

A sudden cardiac arrest is just that — sudden, unexpected. And while you can’t predict when one might strike, you can plan your response. That’s where the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin is making a difference.

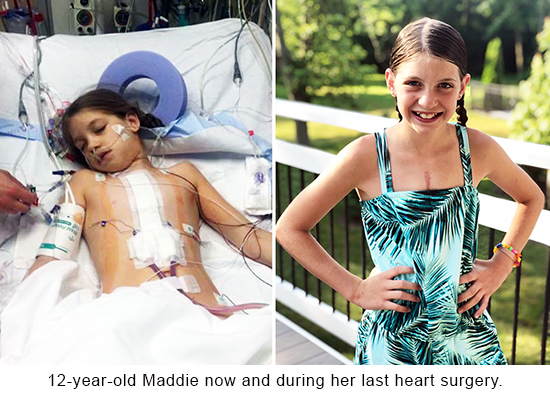

Maddie’s story

While all this was going on at Franklin High School, a few miles down the road, 12-year-old Maddie was sitting in class at Forest Park Middle School. Maddie and Hunter didn’t know each other, but that morning their lives would be forever linked.

While all this was going on at Franklin High School, a few miles down the road, 12-year-old Maddie was sitting in class at Forest Park Middle School. Maddie and Hunter didn’t know each other, but that morning their lives would be forever linked.

Maddie was born with several serious heart defects. The primary condition is known as unbalanced atrioventricular canal, a serious defect in which the left side of her heart and the internal walls separating the upper and lower chambers didn’t fully develop. Maddie had three open-heart surgeries — at 2 months, 4 years and 8 years old. While these surgeries restored her heart’s function, they did not “cure” the heart disease.

The last 10-20 years have seen remarkable medical advancements for kids born with heart defects. Not too long ago, kids like Maddie rarely survived, certainly not long enough to attend school. But now they’re living well into adulthood and with each barrier they break down they’re facing new, previously unforeseen health complications and challenges.

1

“When a baby has a heart defect, they have oxygen-depleted blood circulating through their body. The brain is not receiving enough oxygen,” said Christie Ruehl, a School Intervention Program coordinator. “As a result, kids born with heart defects often experience neurodevelopmental delays later in life.”

As this new population of congenital heart disease survivors grows up and heads to school, they pose unique challenges for teachers. Many of these children will experience speech and language difficulties, learning and cognitive delays, behavioral or emotional concerns and struggle with fine and gross motor function.

In 2015, the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin started the School Intervention Program to address these very issues. When a child is enrolled in this program, they are assigned a school intervention specialist. That person serves as a communication hub for the child, their school and the hospital and works collaboratively with all parties to boost academic success, motivation, attendance, attention, behavior and social-emotional functioning. This free program advocates for the school needs of cardiac patients from preschool-age though college.

In 2015, the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin started the School Intervention Program to address these very issues. When a child is enrolled in this program, they are assigned a school intervention specialist. That person serves as a communication hub for the child, their school and the hospital and works collaboratively with all parties to boost academic success, motivation, attendance, attention, behavior and social-emotional functioning. This free program advocates for the school needs of cardiac patients from preschool-age though college.

For Maddie, academic and social struggles led to behavior issues. For example, she has spatial and sensory sensitivity. So when a classmate would get too close to her or there would be a lot of noise or commotion in class, Maddie would act out.

“I just think the school didn’t understand how it was all connected to her heart condition,” said Nicole, Maddie’s mom.

In early 2019, Maddie was assigned to Christie, who met with Maddie, her parents, her teachers, the school nurse and principal three times that spring. In those meetings, Christie outlined Maddie’s extensive medical history, detailed some of her neurodevelopmental diagnoses and recommended changes to her individualized education plan (IEP).

“Christie did a great job. She was able to explain how kids like Maddie learn and thrive and the importance of the support and why she needs it. She really opened their eyes,” said Nicole. ““And it has absolutely helped Maddie. She has really thrived on those supports that Christie has helped facilitate for us.”

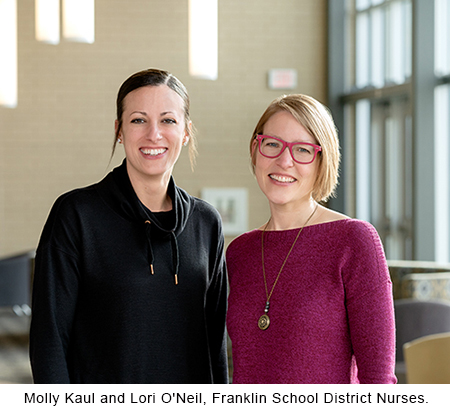

“It was great for them to share more in-depth medical information,” said Lori O'Neil, BSN, RN, a Franklin Public Schools nurse. “That information was helpful for school staff to know how to care for Maddie not only from a medical standpoint, but just her overall health.”

While the school was open to getting Maddie the help she needed to succeed academically and socially, an equally important component of the School Intervention Program is to ensure staff knew how to respond in the event Maddie had a cardiac incident at school.

Enter Project ADAM and Heart Safe Schools.

One boy’s enduring legacy

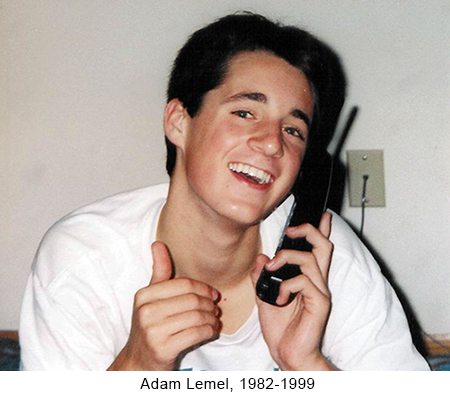

On January 22, 1999, another 17-year-old high school student collapsed at a school in Whitefish Bay. He had a sudden cardiac arrest while playing basketball and did not survive. His name was Adam Lemel.

On January 22, 1999, another 17-year-old high school student collapsed at a school in Whitefish Bay. He had a sudden cardiac arrest while playing basketball and did not survive. His name was Adam Lemel.

If there had been an AED at the school or more people trained in CPR, Adam’s outcome may have been very different. In the wake of Adam’s untimely and unexpected death, his parents, Patty and Joe, committed their lives to doing whatever they could to make sure no one else would suffer the same fate.

In 1999, Adam’s parents started Project ADAM (Automated Defibrillators in Adam’s Memory) in partnership with the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin. Because approximately 20 percent of a community is in its schools on any given day — including students, teachers, staff and family members — Project ADAM believes school preparedness is critical. The program not only helps schools obtain AEDs, but also arranges AED/CPR training to staff and offers free assistance in creating cardiac emergency response plans. Once a school successfully implements those criteria, they are designated as a “Project ADAM Heart Safe School.”

To date, there are 25 Project ADAM affiliate programs in 20 states. Together, they have designated more than 3,150 “Heart Safe Schools” across the nation and saved more than 150 lives.

When Christie met with Lori and other officials from the Franklin School District to go over Maddie’s care plan, she learned that while the school did have AEDs on campus, not everyone knew how to use them. Additionally, though the school district did conduct two emergency response drills a year, they did not always involve a response to a sudden cardiac arrest.

While Lori oversees the district’s five elementary schools, fellow school nurse, Molly Kaul, MS, RN, PCNS-BC, covers the middle and high school. Both having previously worked at Children’s Wisconsin, they knew well the many different types of health conditions that could suddenly arise and need an emergency response. The two had been working for years to raise awareness of different types of medical emergencies and improve the school’s emergency response plans. They trained for everything from kids having a seizure to a diabetic episode to a severe allergic reaction.

While Lori oversees the district’s five elementary schools, fellow school nurse, Molly Kaul, MS, RN, PCNS-BC, covers the middle and high school. Both having previously worked at Children’s Wisconsin, they knew well the many different types of health conditions that could suddenly arise and need an emergency response. The two had been working for years to raise awareness of different types of medical emergencies and improve the school’s emergency response plans. They trained for everything from kids having a seizure to a diabetic episode to a severe allergic reaction.

But after meeting with Christie, they saw the need to develop a thorough cardiac specific plan.

“It was good for us to make sure we had specific cardiac protocols in place,” said Molly. “Now we are always sure to include CPR and AED training in every drill, no matter the nature of the emergency.”

2

On December 17, 2019, the Franklin School District achieved its “Project ADAM Heart Safe School” designation. No one knew at the time that all their training would be put to the test just two weeks later.

“You really don’t understand or appreciate it until something happens close to home,” said Scott, Hunter’s dad. “It’s like fire drills. They can become mundane and you ask, ‘Why do we do this all the time?’ Well, this is why.”

Skill, not luck

Around 2 p.m. on January 2, Hunter awoke in a hospital room. He has no memory of the incident — no memory of going to school that morning, of collapsing in class, of his friends and teachers rushing to save his life. Nothing.

Around 2 p.m. on January 2, Hunter awoke in a hospital room. He has no memory of the incident — no memory of going to school that morning, of collapsing in class, of his friends and teachers rushing to save his life. Nothing.

“It’s still hard to believe what happened. It doesn’t even seem possible,” said Hunter. “I’m very grateful for the people that helped out since the situation could have been a lot worse.”

Though Hunter was discharged from the hospital on January 7, doctors are still working to determine the exact cause of the cardiac arrest. Hunter has always been healthy and active — he’s a black belt in taekwondo, loves to go hiking, used to play football. He has no prior history of heart issues and structurally his heart is perfectly normal. Additionally, a standard toxicology test performed at the hospital came back negative. Since Hunter was adopted from Russia when he was 2 years old, determining any potential genetic factors will take some time. While doctors expect him to make a full recovery, they have implanted an internal defibrillator to help prevent another cardiac incident from occurring.

The one thing doctors do know for sure is the quick action of Ryan, Jordan and the rest of Franklin High School’s emergency response team saved Hunter’s life.

“The education and training saved his life,” said Jordan. “We took action because we were prepared, empowered and confident to do so. It was pure intensity and chaos but no one was panicking.”

“The education and training saved his life,” said Jordan. “We took action because we were prepared, empowered and confident to do so. It was pure intensity and chaos but no one was panicking.”

“Hunter’s emergency went as well as it did because we practice with the Franklin Fire Department. It’s extremely valuable,” said Lori. “We can’t thank them enough for their partnership. It’s a key piece that I’m really, really grateful for.”

At 7 a.m. on Monday, January 13, Hunter returned to school, ready to continue his life that was almost taken from him. Three miles down the road, Maddie was getting ready for another day, armed with the resources and tools she needs to be successful. And in thousands of schools across the country, kids were walking the halls with Adam’s eternal legacy protecting them.

Children’s Wisconsin, the Herma Heart Institute, the School Intervention Program, Project ADAM, the Franklin Public School District, the Franklin Fire Department — the impact of these community partnerships knows no bounds. And for Maddie and Hunter, and so many other kids, the impact is all too real.

“The doctors said Hunter was lucky,” said Scott. “But that was the well-trained personnel. There was no luck involved in saving his life.”